I’m a Carrier for a Genetic Disease – Now What?

Receive answers to your questions about being a carrier for a genetic disease, from guest blogger, Christina Barnes

You’ve had genetic testing done, either prenatally or while pregnant, and find out you’re a carrier for a genetic disease. Now what? Results like this can be overwhelming, difficult to understand, and raise a lot of complicated questions. Before you start typing the name of that genetic disease in Google, check to see if the company that completed your test has a genetic counselor on staff to help you interpret your results. Most genetic testing companies have genetic counselors available for consultations to address specific questions about you, your partner, the diseases on your report, and anything else you might need to know. If that isn’t an option, ask your OB-GYN or midwife about your options for genetic counseling.

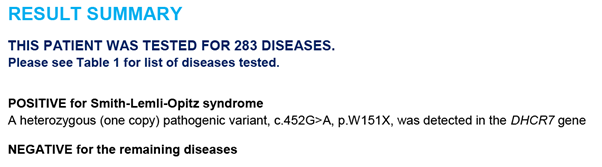

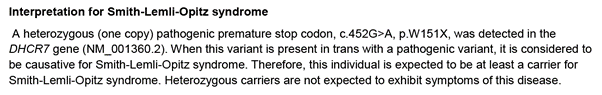

Before my husband and I started trying to conceive, we both had genetic testing done to determine our carrier status. My results came back positive for Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, a disease I had never heard of before. We’ll go through some of the most commonly asked questions about being a carrier and use my report and experiences as an example.

What does being a carrier for a genetic disease mean for you: What is your risk for getting sick?

Smith-Lemli-Opitz is a recessive disease. In order to be affected (sick) with a recessive disease, an individual needs two copies of the mutated gene, one from each parent. As a carrier, I only have one copy of the gene and am therefore unaffected. I do not have any symptoms of this disease, and I never will. Note the last sentence of the interpretation section of my report below:

For a dominant genetic disease, such as Marfan syndrome or Huntington’s disease, only one copy of the mutated gene is needed in order to cause the disease. Individuals who have one mutated gene for a dominant disease will have the disease or will be at an increased risk for having the disease. Dominant conditions are not included in the carrier screening panels people have done before they have children. These diseases are typically tested only on people who are already showing symptoms of the disease. In this case, a special test is ordered by their provider for the purpose of diagnosing that specific disease.

What does being a carrier for a genetic disease mean for your children: What is the risk of having a sick child?

If one parent is a carrier of a recessive disease and the other parent is negative, the child has a 50% chance of becoming a healthy carrier of the disease. For example, my husband tested negative for Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, so our child has a 50% chance of inheriting one defective gene from me. Our child would then be an asymptomatic carrier, just like myself. In this situation, there is an extremely low risk of the child inheriting one copy of the defective gene from each parent, and thus an extremely low risk of having the disease. Why is this risk not zero? I’ll cover that in the next question.

If both parents are carriers of a recessive disease, the child has a 25% chance of inheriting the defective gene from both parents and thus having the disease. The child has a 50% chance of becoming an asymptomatic carrier with one copy of the defective gene, and a 25% chance of inheriting no copies of the defective gene.

If one parent has an affected gene for a dominant disease, the child has a 50% chance of inheriting that dominant gene. If a child inherits one gene for a dominant genetic disease, that child would have the disease or would be at an increased risk for having the disease.

If I test negative, does that mean I am definitely not a carrier?

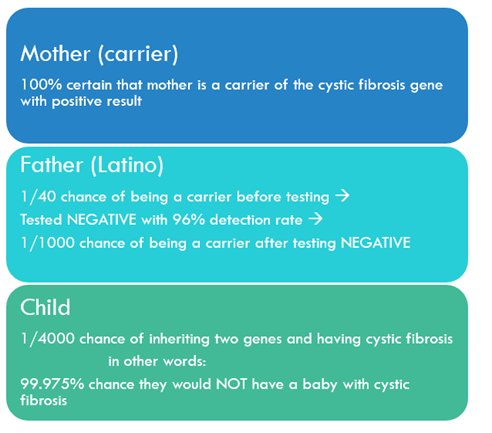

The short answer is NO: even if you test negative, there is still a small chance that you might be a carrier for that disease. A negative result reduces your risk, but it does not eliminate your risk. This is because no genetic test has a 100% detection rate; meaning, no genetic test can detect every single person who is a carrier for a genetic disease. The detection rate varies based on the disease tested, with a range generally between 70 and 99 percent. The rarer the disease, the lower the detection rate. The risk varies depending on ethnic background; in cystic fibrosis, for example, the risk of being a carrier is higher for Caucasians than it is for Latinos.

A positive result, however, means that you absolutely carry that genetic disease. A positive result is 100% accurate.

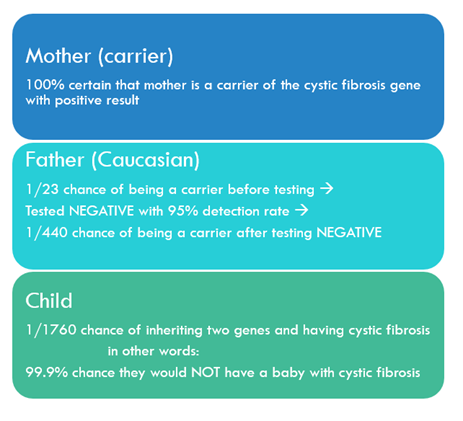

This idea of risk even with a negative result can feel very counter-intuitive. What’s the point of getting genetic testing if it can’t tell me my negative carrier status with 100% confidence? Let’s walk through an example together for Cystic Fibrosis to understand how knowing your reduced risk may still be helpful.

In this example, the mother is a carrier of the cystic fibrosis gene, and the Caucasian father tests negative. A negative test result means that the father still has a 1/440 chance of being a carrier for cystic fibrosis because the genetic test only detects 95% of positives. Even though the father still has a small risk of being a carrier, his negative genetic test reduces their risk of having a child with cystic fibrosis to less than 1/10th of 1 percent.

When we repeat this example with a Latino father, the risk drops even lower because Latinos are less likely to be carriers of cystic fibrosis than Caucasians.

Do my children need to worry if I am a carrier for a genetic disease?

According to Fairfax Cryobank genetic counselor Suzanne Seitz, the vast majority of people who have this testing find out that they’re a carrier for something. “Having a positive result is not unexpected,” she says. “We all can be carriers for several genetic conditions, and this should not be a surprise.” Our children do have some risk of inheriting the recessive genes and being carriers depending on their parents’ status, but as a carrier of only one copy of the gene, they will stay healthy.

“It only matters if we are a carrier for the same condition our partner is a carrier for,” says Suzanne. My son has a 50% chance of being a carrier for Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, but since my husband tested negative for that disease he has an extremely low risk of inheriting the gene from both of us. When my son decides to have children, he and his partner should undergo genetic testing to make sure they are not both carriers for the same disease. If they are, their OB-GYN and genetic counselor can help create the best reproductive plan for them.

When is the ideal time to have genetic carrier testing done?

“Timing is important,” says Suzanne. “Start early. If you have your testing done several months before you start trying to get pregnant, you will have enough time to process the information, avoid stress, stay in control, and make the choices that will help you have a healthy child. If I do find out I am a carrier, that will leave me plenty of time to get my partner tested.” If using an egg or a sperm donor, you can find one that has already tested negative for a specific disease. With the help of the egg or sperm bank, you can also coordinate additional testing done if he or she has not yet been tested for the disease in question. “That way,” Suzanne says, “when you start trying to conceive, these questions about carrier status will already be addressed.”

For more information on on genetic testing and Fairfax Cryobank’s genetic services, please visit our resource page!